Why Liz loves Celtic coins

What’s so special about Celtic coins? What’s making them increasingly popular with collectors all over the world? We all have our own reasons for liking Celtic coins. Here are mine, says Elizabeth Cottam.

Celticity

I love the Celticity of Celtic coins. They were produced by peoples who all spoke Celtic, the old mother tongue of so many countries in Europe. Did you know that the earliest recorded Celtic language comes from Spain?

Primal antiquity

I love the primal antiquity of Celtic coins. Mostly over 2,000 years old, they were the first coins made in England, the first in France, the first in Belgium, the first in Germany, the first in Switzerland, long before these nations had a national identity.

Massalia – inspired a Cantian king to mint the first coins made in

Britain. Found near Chichester, W.Sussex, 7.10.1998. Others found in Kent.

Vast Variety

I love the vast variety of Celtic coin types. Before I joined Chris Rudd in 1998 I’d no idea there were so many. Britain alone minted 1,000 different types, as you’ll see when you look at Ancient British Coins (Chris Rudd 2010) which I co- authored. Meanwhile you can view some typical examples from each tribe.

Tribal vibe

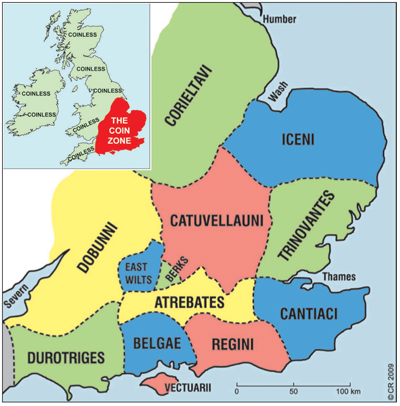

I love the tribal vibe of Celtic coins, with each tribe having its own distinctive coinage, so unlike the blanket blandness and universal uniformity of national coins today. Some coins carried tribal symbols. For the approximate location of the sixty tribes of Britain and Ireland, including those that minted coins, plus possible mint sites, see my map Tribes of the British Isles.

(Cantiaci much earlier). Tribal names, recorded in the Roman era,

may not be accurate. Tribal boundaries, as shown here, are speculative.

Regality

I love the regality of Celtic coins – rulers regaled with royal coronets, diadems and golden neck torcs symbolic of their sacral kingship. The very sound of their cocky monickers – Dubnovellaunos ‘ruler of the world’, Addedomaros ‘great in chariots’ – is cheering to my ears. You’ve heard of King Arthur, King Alfred and William the Conqueror. But how many pre-Roman rulers can you name? Two? Five? Ten? See my table of Ancient British kings.

money’ minted mainly for the ruler’s personal benefit, whether to pay troops or tribute,

buy royal goods or services, curry favour with peers or proles, or bribe the gods. This gold

stater, ABC 2774, was struck at Camulodunon (Colchester, Essex) for King Cunobelinus

‘hound of Belenus’, the most potent tribal king of his time – the most powerful in Atlantic

Europe – who personally controlled more land, more lives and more wealth by AD 41 than

any other tribal leader west of the Rhine. Chris Rudd List 54, 2000, No.75, £2000.

Freedom fighters

I love the freedom fighters on Celtic coins, those brave warrior-kings and warrior-princes who opposed the power of Rome, like Vercingetorix and Caratacus.

Roman love affair

I love the Roman love affair that other Celtic rulers had, importing fine Italian wine and silver tableware and copying Roman coins.

(ABC 2960), the Roman god Janus (ABC 2981) and a Roman-style

laureate head (ABC 2957). The third coin was found near Ware, Herts., 1973.

Handsome heads

I love the handsome heads on Celtic coins – stronger, stranger, wilder, weirder, more fantastic, more surrealistic than any other heads you see on any other coins.

silver unit, ABC 686, with holed Selsey Cernunnos silver unit, ABC 680,

both struck by the Regini of W.Sussex, c.55-40 BC.

Amazing menagerie

I love the amazing menagerie of creatures on Celtic coins, from bulls and boars to stags and starfish.

found by metdet Scott Larcombe, near Lowestoft, Suffolk, 2011. This is my favourite

Celtic coin. Look at those large sharp teeth, those spiky bristles and those ‘man bits’

under the wolf’s shaggy tail. Can you see the bird perched on his rump? See Rainer Kretz,

On the track of the Norfolk Wolf, Chris Rudd List 48, and Dr Daphne Nash Briggs,

Some cosmic wolves, in Chris Rudd List 110, p.2-4.

Imaginative imagery

I love the imaginative imagery of Celtic coins. This was Britain’s golden age of daring coin design, as we say in Britain’s First Coins (Chris Rudd 2013). To get a sense of how innovative Britain’s tribal coins were – each region developed its own local style – see Some typical examples from each tribe.

introduction” says David Sear.

Mythic mystery

I love the mythic mystery of Celtic coins. I catch glimpses of long-lost legends and ancient pagan rituals, such as head hunting and bull sacrificing. I feel the power of Druid priests who probably influenced the design of many Celtic coins.

(ABC 1235) and a severed head being carried (ABC 2987).

Miniature masterpieces

I love the miniature masterpieces of Celtic coins, especially those of silver minims. How did the ancient Brits manage to get so much detail onto an 8mm coin (smaller than my smallest fingernail)? How did they standardise the weight at ¼ gram?

Hidden humour

I love the hidden humour of Celtic coins – all those smiley faces and those ‘now-you-see-it-now-you-don’t images’ as Van Arsdell calls them.

Astonishing astrology

I love the astonishing astrology of Celtic coins – the galaxies of suns and moons and stars that shine and twinkle on hundreds of Ancient British coins. Once again I sense the shadowy presence of Druids.

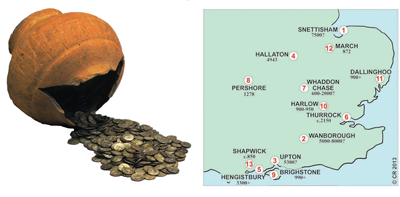

Hoary hoards

I love the hoary hoards of Celtic coins that keep hitting the headlines. No banks in those days, no ‘hole in the wall’ ATMs. So I guess folk had no choice but to dig a hole in the ground.

Uniqueness

I love the uniqueness of many Celtic coins, the exciting exclusivity of holding the only known example of an Ancient British coin in my hand. Such remarkable rarities never cease to thrill me.

Historical importance

I love the historical importance of Celtic coins – the fact that they are helping to rewrite the history of Britain in the late Iron Age. Many of its rulers are known solely from their coins.

Foxy old forgeries

I love the foxy old forgeries of ancient Celtic counterfeiters. With matchless metallurgy and unrivalled guile they managed to make plated gold staters look and feel like solid gold staters.

would doubtless have deceived anyone who handled it because it would have looked and felt just

like a genuine gold stater issued by the royal mint. Inamn Tree bronze stater core, c.AD 1-20?,

ABC 2060, found at Hod Hill, Dorset, 1862, and now in the British Museum where it won’t

fool anyone. Photo © Institute of Archaeology, Oxford.

Unpredictability

I love the unpredictability of Celtic coins. New types keep leaping out of the soil. Attributions, names and dates are always being revised. Celtic studies are in a constant state of flux. Want to see three surprises?

Uncommon scarcity

I love the uncommon scarcity of Celtic coins. Ask any metdet how many Ancient British coins he or she has found and you’ll immediately realise that they are much rarer than Roman coins – at least a thousand times rarer on average.

Galloping good value

Finally, I love the galloping good value of this horsey money. Their greater rarity doesn’t mean that Celtic coins are costlier than other ancient coins. In fact, they are often cheaper. For example, a very fine British gold stater typically costs less than half the price – sometimes even a third of the price – of a Roman aureus or English gold noble of comparable quality and rarity. Celtic coins are, in my opinion, undervalued coins.

Brigitte and you

Now you know why I, a Celtic dealer, love Celtic coins. If you want to know why a Celtic scholar fancies them, a friend of mine will tell you. See Dr Brigitte Fischer, Why I like Celtic coins, in Chris Rudd List 59, 2001, p.2-4. How do you feel about Celtic coins? And how can I make this website more helpful to you? Please tell me. liz@celticcoins.com